The Price of World Isolation

What Hitler’s first economic move reveals about fear, power, and the seduction of self-sabotage.

Hey Small Biters,

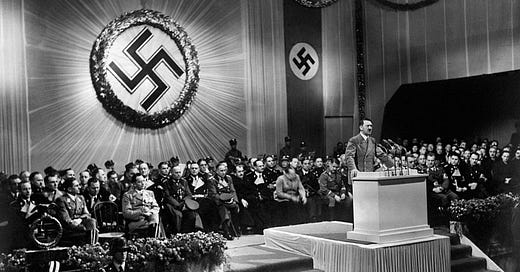

There’s a moment — early in power — when every leader shows you who they are. For some, it’s a speech. For others, a war. But for Hitler? It was tariffs.

In 1933, just days into his rule, Hitler’s government began raising trade barriers and hiking import duties on basic goods. These weren’t subtle tweaks. They were sweeping, immediate acts of economic self-isolation — cheered by nationalists, feared by economists, and devastating to Germany’s recovering public.

The rationale? According to Hitler and his economic ideologue Gottfried Feder, Germany had been weakened by foreign trade. Feder’s racist worldview described global commerce as infiltration — an erosion of German blood and dignity, especially by “Negroes, coolies, and Soviet slaves,” in his abhorrent phrasing. To sever those ties was, in their eyes, not just prudent policy — it was purification.

But here’s the truth behind the headlines: Germany wasn’t failing. It was healing.

When Hitler became chancellor, the German economy was on the rebound. The worst of the Great Depression had passed. The stock market jumped on his appointment. Unemployment was falling. And crucially, Germany’s export industries were finding footing again — with foreign markets as their customers.

Yet instead of stabilizing this recovery, Hitler destabilized it. His tariffs drove up prices and strained Germany’s supply chains. Eggs became 600% more expensive. Trade partners retaliated. German farmers, promised protection, couldn’t afford equipment or imported feed. Industries lost overseas buyers. Jobs disappeared.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Small Bites to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.